|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Brief Review on Advanced Metallic Materials Advanced Nonequilibrium

Materials,

Crystallization leading to

the formation of

Metallic Nanomaterials

Metallic Glassy – (Quasi,Nano)Crystal Composites

Active research activities on metallic glassy alloys (or metallic glasses) started after the formation of the first Au-Si sample with an amorphous structure in 1960[1] by rapid solidification. This become possible by using a rapid solidification technique for casting of metallic liquids at a very high solidification rate of 106 K/s[2]. For a long time Pd-Cu-Si and Pd-Ni-P were known to be the best metallic glass formers[3] . A large number of bulk glassy alloys (also called bulk metallic glasses) defined as 3-dimentional massive glassy (amorphous) articles with a size of not less than 1 mm in any dimension have been produced during the last 30 years. These alloys become widely studied in 90-th. The high glass-forming ability achieved at some alloy compositions has enabled the production of bulk metallic glasses in the thickness range of 1-100 mm by using various casting processes[4],[5],[6]. Production of Glassy Alloys and Their General Features

Much more productive is rapid (compared to conventional metallurgical methods) solidification of a liquid phase[15],[16] by melt-spinning, Cu-mold casting, liquid forging and so on. For example, Al-RE-TM (RE-rare earth metals, TM-transition metal) system glassy alloys[17],[18] were produced in a ribbon shape by the melt spinning technique[19] or as powder using gas atomization technique[20] as well as binary Al-RE alloys[21],[22]. An addition of Co partially replacing Y in the Al85Y10Ni5 (here and elsewhere alloy compositions are given in nominal atomic percents (at.%)) increased tensile fracture strength without worsening of bend ductility[23]. Al85Y8Ni5Co2 alloy exhibits one of the largest supercooled liquid region on heating among the Al-based metallic glasses. A partial substitution of Y by Mischmetal (Mm), a natural mixture of the RE elements, leads to a drastic decrease in the alloy cost without significant deterioration of the mechanical properties[24],[25]. Although ease of devitrification of the Al-based glassy samples connected with a high density of so-called quenched-in nuclei in some glasses as well as a low reduced glass-transition and devitrification temperature in the other glasses[26], in general, impedes a limit on the sample’s critical thickness below 1 mm bulk amorphous samples of high relative density were still obtained by warm extrusion of atomized amorphous powder[27]. Bulk glassy alloys obtained

in the late 80-th (except for Pd-Cu-Si and Pd-Ni-P

obtained earlier2,3) with an extraordinary high GFA[28],[29],[30]

have larger size (comparable with conventional crystalline alloys)

of 1-100 mm. They can be obtained at the cooling rates of the

order of

100, 10, 1 K/s and even less[31],[32] much lower than 104-106 K/s required

for

vitrification of marginal glass-formers. The bulk glassy alloys possess

three

common features summarized by Inoue[33],

i.e., belong to multicomponent systems, have significant atomic size

ratios of

above 12% and exhibit negative heats of mixing among the constituent

elements. Cu-based bulk

glassy alloys wereobtained not only in the

ternary

Cu-(Zr or Hf)-Ti

[34]

but even in the binary Cu-(Zr or Hf)34,

[35]

,

[36]

,

[37]

systems. An

addition

of the third element like Ti or Al, for example,34 enhances

the

glass-forming ability of a binary alloy in accordance with the

“confusion”

principle which postulates that the multicomponent alloys in general

posses

better GFA than the binary alloys

[38]

.

Bulk glassy alloys exhibit high strength, hardness, wear resistance and large elastic deformation

(Fig. 2) and

high corrosion resistance , including passivation in some

solutions[39],[40].

Pt-based bulk metallic glass was reported to exhibit a

room-temperature strain of 20 % due to a high Poisson ratio of 0.42[41].

Bulk glassy alloys can be

thermo-mechanically shaped or welded in the supercooled liquid region.

Electromechanical shaping technology allows their rapid shaping by

Joule

heating at low applied stresses due to the high electrical resistivity

of

glassy alloys[42],[43].

Bonding of glassy alloys can also be achieved by friction welding[44].

Moreover, glassy alloys also exhibit superplasticity[45]

including

high-strain-rate superplasticity[46].

Glass-Forming Ability and General Properties In general bulk glassy alloys are formed at the compositions with high Tg/Tl (Tg glass-transition temperature, Tl liquidus temperature) (Fig. 3) ratio exceeding approximately 0.6[47],[48]. At the same time, it has been shown that the width of the supercooled liquid region (dTx) (defined as Tx-Tg where Tx is onset devitrification temperature) as indicator of the stability of the supercooled liquid against devitrification also correlates quite well with GFA . The parameter gamma=Tx/(Tg+Tl) takes into account both criteria[49] as high Tx and low Tg+Tl values leading to high gamma parameter indicate rather low Tl and high dTx values. The best glass-forming compositions are not at the equilibrium eutectic point but somewhat shifted usually towards more refractory component [50] , while Tg is not significantly different in the observed range. This is most likely due to the shift of the eutectic point with undercooling at high enough cooling rate as casting conditions of bulk glassy samples are far from the equilibrium conditions. This may be a result of deep undercooling or existence of the competing crystalline phases in the system. Both factors may cause a shift of the eutectic point. However,

the principles for achieving a good GFA known so far are rather

indispensable

conditions which sometimes, however, are not sufficient[51].

The addition of Nd caused formation of an amorphous single phase only

in the

Ge-Ni-Nd alloy while no amorphous phase was formed in the Si-Ni-Nd

alloy. It

was found that the higher GFA of the Ge-Ni-Nd alloy compared to the

Si-Ni-Nd

one cannot be explained on the basis of the widely used parameters,

geometrical

and chemical factors, viscosity and diffusion data. It was suggested

that the

electronic structure characteristics, for example electronegativity

difference,

should be taken into consideration51.

It has been shown that the electronegativity[52] of the constituent elements is an important factor influencing glass formation and the temperature interval of the supercooled liquid region of the glass-forming alloys[53],[54]. Packing

density for non-crystalline structures, as a geometrical

factor influencing GFA, has been verified using hard spheres model[55],[56].

A mixture of atoms with different sizes enables their more dense

packing than

can be achieved with separate phases. An importance of efficient atomic

packing

for the formation of metallic glasses was shown recently[57],[58].

It has been emphasized that specific radius ratios are preferred in the

compositions of metallic glasses. This features are also closely

connected with

so called l criterion

for good glass-forming ability[59],[60].

It

has been also supposed that electron concentration: number of valence

electrons

per number of atoms (e/a value) affect glass-forming ability[61],[62].

By

other words good glass-formers have definite electron concentration

values.

This rule has been proposed by analogy with Hume–Rothery phases related

to

certain valence electron concentration. However, as many glassy alloys

contain

transition metals which have multiple valencies, it is difficult to

decide

which valency value should be taken into consideration in a particular

case.

The

glass-transition

phenomenon in metallic glasses has been studied extensively. Three kinds of approaches have been formulated (see[63],[64], for example, among the other sources): (1) glassy phase is

just a frozen liquid, and thus, glass-transition is a kinetic

phenomenon and no

thermodynamic phase transformation takes place; (2) glass-transition

may be a

second-order transformation as follows from the shape of the curves for

the

thermodynamic parameters, for example, specific volume or enthalpy,

which

exhibit a continuity at the glass-transition temperature while their

derivatives like dV/dT or dCp/dT exhibit a discontinuity (in a

certain

approximation) at the glass-transition temperature; (3)

glass-transition may be

a first-order transformation as follows from the free-volume model.

Devitrification/Crystallization of Glassy Alloys Leading to Formation of a NanostructureNanoscale particles of a crystalline or a quasicrystalline phase can be readily formed by devitrification of the glassy alloys. This indirect method of production of the nanostructure requires formation of the glassy phase in the initial stage and its subsequent full or partial devitrification on heating. Such a method leads to the formation of a highly homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles in various alloys. Nevertheless, a nanostructure can also be obtained directly during rapid solidification or casting at a certain cooling rate used. However, in such a case it is often difficult to adjust an appropriate cooling rate and to obtain a homogeneous structure. Matrix phase prior to devitrification

can be amorphous, glassy or supercooled liquid. Although it might be

difficult

to establish an intrinsic physical difference between amorphous and

glassy

alloys such a slightly arbitrary differentiation is useful, especially

in

relation with devitrification behaviour. Here we define an alloy being

“amorphous” if it does not transform to a supercooled liquid before

devitrification (Fig. 3). In general glassy alloys exhibiting the

supercooled

liquid region on heating prior to devitrification have better

glass-forming

ability compared to amorphous alloys.

Alloys devitrifying from the supercooled liquid exhibit a tendency to form metastable phases and phases with high crystallographic symmetry on devitrification[67]. It may be connected with the change of the local atomic structure in the supercooled liquid region due to higher atomic mobility compared to that in the glassy phase. Below Tg the crystalline products of devitrification inherit the as-solidified structure of the metallic glass. Four types of phase transformations were found to occur during devitrification of the glassy alloys: polymorphous (a product phase has the same composition as the glassy phase), primary (a product phase has a composition different from that of the glassy phase), eutectic devitrification (two or more phases nucleate and grow conjointly) and spinodal decomposition involving a phase separation of the glassy phase prior to devitrification. If devitrification occurs by nucleation and growth mechanism (amorphous alloy does not have pre-existing nuclei), then high nucleation rate leading to high number density of the precipitates of the order of more than 1021 m-3 and low growth rate of the precipitating phase are required in order to obtain a nanostructure. The nucleation and growth processes leading to the formation of a nanostructure, including transient nucleation have been described in detail in several earlier works[68],[69]. The kinetics of the devitrification process has been also analyzed[70],[71]. Devitrification of glassy alloys can be analyzed by Kolmogorov[72] -Johnson-Mehl[73] –Avrami[74] -Kelton[75] general exponential equation for the fraction transformed x(t):

where I and u are nucleation and growth rates, respectively, while n is the Avrami exponent. Nanostructured alloys are readily obtained on primary devitrification of glasses with a long-range diffusion controlled growth[76]. Another type of phase transformation in an amorphous solid leading to formation of a nanostructure is spinodal decomposition[77],[78]. For instance, it has been reported that in some Al–TM–RE glasses devitrification leading to formation of a nanostructure appears to be preceded by the amorphous phase separation[79],[80]. Nevertheless, the most common mechanism

leading to formation of a nanostructure is primary devitrification. fcc a-Al lattice

parameter measurements and atom probe

ion field microscopy investigation[87]

showed

very low concentration of the alloying elements in nanocrystalline Al

in

accordance with the phase diagrams[88]

of Al-RE

and Al-TM. Segregation of the RE metal having low trace diffusivity in

Al on

the a-Al/amorphous phase interface

is

considered to be one of the most important reasons for the low growth

rate of a-Al. It is also important to note that

the primary devitrification requires a long-range diffusion that

impedes

crystal growth[89].

Clear

heterogeneous nucleation was observed during formation of the a-Fe nanocrystals[90],[91].

The structure of Fe-based soft magnetic alloys like: Finemet Fe73.5Cu1Nb3Si13.5B9[92]

and

Nanoperm Fe84Zr3.5Nb3.5B8Cu1[93]

after

annealing consists of bcc Fe nanocrystals below 20 nm in size finely

dispersed

in the amorphous matrix. Cu, Nb or Zr elements despite on their low

contents

are responsible for the formation of a nanostructure upon annealing.

For

example, devitrification of the Fe73.5Cu1Nb3Si13.5B9

alloy, which initially has an isotropic amorphous structure, starts

from the formation

of Cu-enriched zones[94].

As has been shown by means of atom

probe field ion microscopy as well as by high resolution transmission

electron

microscopy[95]

Cu forms nano clusters in the Fe73.5Si13.5B9Nb3Cu1

amorphous matrix which act as the sites for heterogeneous nucleation of

the bcc

Fe particles on devitrification[96].

The

density of the clusters estimated by three dimensional atom probe is in

the

order of 1024 m-3 at the average cluster size of

about

2-3 nm[97].

Not only pure metals and limited solid

solutions but intermetallic compounds can be formed with a nanoscale

size. For

example, the devitrification of

nanocrystal-forming

Ti-based alloys, for example, the Ti50Ni20Cu23Sn7

alloy begins from the primary precipitation of a nanoscale equiaxed,

almost

spherical particles of cF96 Ti2Ni solid solution phase

(other

alloying elements are partially dissolved in this phase) with a lattice

parameter of 1.138 nm[98],[99].

Formation of such a nanoscale cF96 phase having a large cubic unit cell

has

also been observed in the Zr- and Hf-based alloys[100],[101].

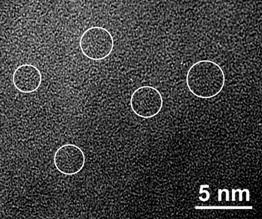

An extremely small size and low growth rate of cF96 crystals were observed in Hf55Co25Al20 glassy alloy. This alloy undergoes a double-stage devitrification forming the primary cubic cF96 Hf2Co phase from the supercooled liquid by the steady state nucleation and diffusion-controlled growth of nuclei followed by the subsequent devitrification of the residual glassy matrix forming Hf2Al and an unidentified phase. The cF96 nanoscale phase has a very low average growth rate of the order of 10-11 m/s. Very small cF96 Hf2Co clusters of 2-5 nm in size are observed in a HRTM image of the annealed sample (Fig. 4). Diffusional redistribution of Al within the glassy matrix may be the reason for the small growth rate of the clusters. It is interesting to note that although this alloy exhibits devitrification by nucleation and growth mechanism the local order of the cF96 clusters is close to that of the glassy phase[102].

In

many cases redistribution of the alloying elements on a short

scale precedes devitrification. For example, Mg-Ni-Mm and Mg-Ni-Y-Mm glassy alloys show a

multistage devitrification behaviour[103].

The amorphous Ge-Cr-Al-RE

alloys also exhibit local order changes prior to nanoscale

devitrification. For

example, some structure changes occur in the Ge70Cr16Al10Nd4

alloy prior to devitrification124. Primary Ge nanoparticles

are also

formed in many Ge-Al-Cr-RE alloys[104].

Anomalous X-ray scattering studied shows that Ge-Ge atomic pair in

Ge-Al-Cr

alloy has a different coordination compared to metal-metal and Ge-metal

pairs[105].

The as-solidified microstructure of the rapidly solidified Ge-Al-Cr-RE alloys examined by TEM showed the presence of finely dispersed zones homogeneously distributed in the amorphous matrix[106]. Their size is estimated to be about 1 nm[107]. These zones are responsible for the split of the first diffraction maximum in the SAED and XRD patterns. However, as the ordered zones are as small as 1 nm in size. An intermediate Ge-Ni-La compound which precipitates prior to the equilibrium phases in the Ge60Ni35La5 amorphous alloy may inherit the local atomic order of the amorphous phase [108]. However, in many cases a nano-dispersed structure can be obtained directly from the melt upon rapid solidification by proper alloying. For example, the microstructure of the Si48Al20Fe10Ge7Ni5Cr5Zr5 alloy having an amorphous type X-ray diffraction pattern is inhomogeneous and contains Ge particles of less than 5 nm in size embedded in an amorphous matrix (Fig. 5)[109]. Ge having a lower mixing enthalpy with the other alloying elements than Si is rejected from the amorphous matrix and precipitates forming fine nanoparticles, though it has an unlimited solubility in Si.

Here

one should mention that the factors leading to

nano-devitrification of metallic glasses and amorphous alloys in many

cases are

not fully understood while several reasons are listed in the

literature. They

can be connected with the occurrence of heterogeneities such as oxygen

impurity-enriched clusters[110],

spinodal decomposition in the liquid or glass[111]

and homogeneous nucleation in partitioning systems[112].

The time-temperature-transformation diagrams[113] created in the isothermal mode or under continuos heating are useful for comparison of thermal stabilities of different glasses against devitrification as well as for the selection of the heat treatment regimes. Such diagrams have been created for different metallic glasses[114] [115] [116] [117] [118] [119]. Comparison of the long-term thermal stabilities of different metallic glasses has been done using continuos heating transformation CHT diagrams[120]. CHT diagrams have been constructed by applying a corollary from the Kissinger analysis method using the DSC data at different heating rates. CHT diagrams also can be recalculated from the isothermal ones[121] using a method close to that used for steels[122]. This method was proved to provide a good correspondence between the data at least in the mid-temperature range.

Not

only thermal activation but plastic deformation can cause nanoscale

devitrification of a glassy phase. For example, deformation

of some Al-RE-TM amorphous alloys at room temperature causes

precipitation of deformation-induced Al

particles of 7-10 nm in diameter within the shear bands on

bending[123]

or nano-indentation[124].

It has been suggested that a local temperature rise can play a role in

mechanically-induced devitrification[125].

However, further studies on nano-indentation of glassy alloys at low

strain

rates also showed the formation of the nanoparticles when local rise of

the

temperature due to adiabatic heating is not supposed to take place[126].

This postulate has been confirmed by bending test at low temperature

using dry

ice[127].

Nano-devitrification

leading to formation of quasicrystals An icosahedral quasicrystalline

phase having a long-range quasiperiodic translational and an

icosahedral

orientational order, but with no three-dimensional translational

periodicity

was initially discovered in Al-Mn alloys[128] and later in the other binary Al-TM- based alloys containing Cr[129]

and V[130],[131]

and different ternary alloys[132].

The Al-TM base icosahedral structure has been presumed[133]

to consist of Mackay icosahedral clusters. Later the icosahedral phase was

observed

in

Quasicrystals can coexist with

rational approximant crystalline structures[138].

A

multiple twinning around an irrational axis of the approximants has

been

reported in an aggregate of fine size cubic crystallites[139].

A nanomaterial consisting of almost spherical

icosahedral particles with a diameter below 10 nm was obtained in Zr-Pt

alloy[140]

by

casting. An enhancement of the icosahedral short-range order in

the

supercooled Ti-Zr-Ni liquids decreases the barrier for the nucleation

of the

metastable icosahedral phase, even in the alloys in which the stable

crystalline phases are formed according to the equilibrium phase diagram[141],[142].

Reduced supercooling (undercooling)

before

crystallization from the melt was found to be the smallest for

quasicrystals,

larger for crystal approximants and the largest for crystal phases[143]. A low energy barrier for nucleation of

the icosahedral phase may explain the fact that only growth of the

pre-existed

icosahedral nuclei was observed in the Zr65Ni10Al7.5Cu7.5Ti10Ta10

alloy

[144]

.

Formation of the nanoscale icosahedral phase was observed in the devitrified Zr-Cu-Al, Zr-Al-Ni-Cu[145] and Zr-Ti-Ni-Cu-Al[146] glassy alloys containing an impurity of oxygen above about 1800 mass ppm, although no icosahedral phase is formed if oxygen content is lower than 1700 mass ppm. Recently, the nanoscale icosahedral phase was obtained in devitrified Zr-Al-Ni-Cu-Ag[147], Zr-Al-Ni-Cu-Pd[148], Zr-Ni-NM[149] (NM-noble metals), Ti-Zr-Ni-Cu[150], Zr-Al-Ni-Cu-(V, Nb or Ta)[151], Zr-Pd[152] and Zr-Pt[153],[154] system alloys at much lower (typically about 800 mass ppm) oxygen content. The icosahedral phase is also formed in the Zr70Cu29Pd1 alloy at the very low Pd content[155]. It is also noted that the icosahedral phase precipitates from the supercooled liquid in Zr-based amorphous alloys containing the NM elements. The nanoscale icosahedral phase has been produced recently in the NM-free Zr-Cu-Ti-Ni[156] and Zr-Al-Ni-Cu glassy alloys with low oxygen content below 500 mass ppm. The amorphous (glassy) -> icosahedral phase transformation, for example in a Zr65Al7.5Ni10Cu7.5Ag10 alloy, is not a polymorphous but rather a primary type reaction[157]. This explains the observed low growth rates. The local atomic structures around Pt as well as Zr in the amorphous and quasicrystalline Zr70Al6Ni10Pt14 alloys have been determined by the anomalous X-ray scattering method[158]. Devitrification of several other Zr-based bulk metallic glasses has been also studied in situ using a high energy monochromatic synchrotron beam diffraction in transmission on heating[159]. Transformation

from glassy+beta-Zr to

glassy+icosahedral structure was observed in Zr65Ni10Al7.5Cu7.5Ti5Nb5

alloy on heating by a

single-stage transformation with

diffusion control. b-Zr solid solution particles were found to dissolve in

the glassy phase while

the nanoscale particles of the icosahedral phase precipitate after the

completion

of the first exothermic reaction[160], which is considered to be a single-type

reaction in a certain sense

similar to peritectic one.

In the rapidly solidified TixZryHfzNi20

system alloys the nanoscale icosahedral phase is formed in the

composition

ranges close to the cI2 beta solid solution phase and complex cF96 phase formation ranges[161].

Moreover, cI2 b solid solution

and icosahedral phases were found to have close stochiometric

compositions.

This is not a surprising result as late-transition

metals (LTMs) have a high solubility in the cI2

b phase of

early-transition metals (ETMs).

The nanoscale

icosahedral quasicrystalline phase has been also produced upon heating

glassy

Hf65Pd17.5Ni10Al7.5[162],

Hf65Al7.5Ni10Cu12.5Pd5[163],

Hf59Ni8Cu20Al10Ti3[164]

and Hf65Au17.5(Ni,Cu)10Al7.5[165]

alloys (here and

elsewhere in the paper the (Ni,Cu)

symbol means Ni or Cu). Formation of the nanoscale icosahedral phase has

been also

found at an early devitrification stage of a binary Hf73Pd27

alloy[166].

According to the

quasilattice constant value, the icosahedral

phase in

the Hf65Pd17.5Ni10Al7.5, Hf65Au17.5Ni10Al7.5

and Hf65Au17.5Cu10Al7.5

alloys

consists of 137-atom Bergmann rhombic triacontahedra. However, Hf-based alloys have a

higher tendency to form a cubic cF96 phase compared to Zr-based ones.

The

alloys in the systems in which an equilibrium Hf-based cF96 phase

exists do not

show the formation of the icosahedral phase from the amorphous matrix[167].

The

formation of the nanoscale icosahedral phase was recently

observed in the Cu-based alloys alloyed with Pd[168]

and Au[169]

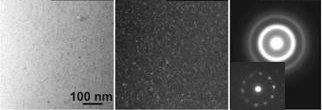

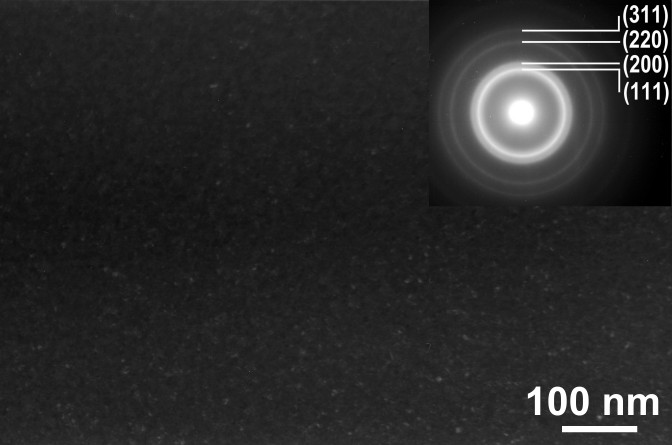

while Ag- and Pt-bearing alloys did not form the icosahedral phase[170].

Replacing 5-10 at.% Cu

with Pd in the Cu60Zr30Ti10

glass-former

changes its devitrification pathway[171],[172],[173], inducing nucleation and

diffusion-controlled growth of a nanoicosahedral phase of about 3-10 nm

in size

(Fig. 6) consisting of rhombic triacontahedra from the supercooled

liquid region in the initial stage of the

devitrification process. A single initial devitrification reaction

takes place

in the Cu55Zr30Ti10Pd5

alloy while

in the Cu50Zr30Ti10Pd10

alloy a

combination of two reactions forming the icosahedral and crystalline

phase

takes place.

The addition of 5 at.% Pd expands significantly the supercooled liquid region in Cu-Zr-Ti alloy[174]. Cu-Zr-Ti[175] alloy contains nanoscale crystalline particles (about 5 nm size) in as-solidified state whereas the alloy containing 5 at.% Pd is amorphous174. Nanoscale particles of the cP2 CuZr phase were observed in the as-solidified Cu50Zr30Ti10Pd10 alloy. The dissolution of the CuZr nanoparticles took place on heating up to supercooled liquid region owing to the instability of the CuZr phase below 988 K[176]. According to the Cu-Zr phase diagram, the CuZr phase undergoes eutectoid transformation at 988 K which is above the supercooled liquid region of the Cu50Zr30Ti10Pd10 alloy (about 750-800 K). The nanoscale CuZr phase becomes thermodynamically unstable and dissolves in the supercooled liquid when atomic diffusivity is enhanced by temperature. One of the reasons is that the energy to form an eutectoid interface in nanoparticles is higher than the energy for dissolution of the nanocrystals. High-Strength Nanocomposites Produced by

Devitrification

Devitrification of the

glassy alloys is the way of production of composite

nanomaterials. Nanocrystalline precipitates increase the room temperature mechanical strength of the Zr-Al-Cu-Pd[179], Zr-Al-Cu-Pd-Fe[180] and (Zr/Ti)-Cu-Al-Ni[181] bulk alloys produced by crystallization of cast glassy samples. The deformation behavior of the partially crystallized Zr-based glassy alloys consisting of a metallic glassy matrix with crystallite precipitates of different shape and size has been studied recently[182].

Some

bulk glassy-crystal composites with enhanced ductility have been

produced by

proper alloying with the elements having zero or positive mixing

enthalpy with

main component, for example, in Zr-[183],[184]

and Cu-based alloys [185],[186].

Al-RE-TM amorphous alloys posses a high tensile strength exceeding 1200 MPa[187] and good bend ductility [188],[189]. The homogeneous dispersion of the nanoscale fcc a-Al particles in an amorphous matrix causes a drastic increase in tensile fracture strength to 1560 MPa[190],[191] . These particles can be formed by controlling the cooling rate upon solidification or by annealing glassy alloys. An optimum strength value was obtained when the volume fraction of a-Al phase reached 25%[192],[193]. The significant decrease in tensile fracture strength by the further increase in Vf is due to the embrittlement of the remaining amorphous phase by the progress of structural relaxation and the enrichment in the solute elements[194],[195]. However, in some cases formation of the primary Al particles was found to deteriorate mechanical properties. Partial substitution of Ni by Cu in the Al85Y8Ni5Co2 metallic glass caused formation of the nanoscale Al particles. However, the tensile strength and hardness values drastically decreased[196]. Cu has much lower absolute value of heat of mixing with Al, Y and Co than Ni[197] that leads to decrement of the interatomic constraint force. Thus, Cu may weaken the interaction needed for the stability of the glass, thus resulting in the disappearance of Tg and precipitation of Al nanocrystals. In addition, the volume fraction of the Al nanocrystals in Al85Y8Ni3Co2Cu2, for example, is much lower than that in the primarily devitrified Al85Y8Ni5Co2 metallic glass[198],[199]. Difference in devitrification pathways of

amorphous alloys depending on

heating rate, temperature and other conditions Al85RE8Ni5Co2 glassy alloys showed precipitation of the a-Al nanoparticles after continuous

heating using DSC at high enough heating rates (0.67 K/s and higher) or

isothermal annealing at the temperature above Tg[200],[201]. At the same time, Y-,

Gd- and Dy-bearing metallic

glasses[202]

as well as the Al85Y4Nd4Ni5Co2[203] showed simultaneous formation of the

intermetallic compound(s) and a-Al nanoparticles, or primary formation of the

intermetallic compound

after annealing below Tg. For example, the Al85Y8Ni5Co2 alloy shows formation of an unknown

intermetallic compound conjointly with a-Al nanoparticles after isothermal annealing up

to the completion of the primary phase transformation below Tg

(Fig. 7). The

intermetallic

compounds are metastable and have a

multicomponent composition. The volume fraction of the intermetallic

compound

is higher than that of a-Al

and the fraction of a-Al

depends on annealing temperature below Tg.

Two crystalline phases: the equiaxed nanoscale Ge particles with the size of about 3-20 nm and relatively large dendrites of a multicomponent Ge18Cr4AlCeSm crystalline phase of about 0.5 mm in size precipitate simultaneously in the Ge68Cr14Al10Ce4Sm4 amorphous alloy on heating by a single-type exothermic reaction[204]. At the same time no eutectic-type coupled growth was observed. Ge and Ge18Cr4AlCeSm phases in many cases have no common interface and are separated by the amorphous matrix. Moreover, the size and the volume fraction of the multicomponent phase depend on the heating rate whereas the size and distribution of the Ge particles are independent of it. It can be suggested that Ge nanoparticles grew from the Ge–enriched zones formed during structural relaxation. Nanocomposites produced

in-situ by rapid solidification. The Al-Y-Ni-Co-Pd ribbon samples

have been produced by the melt-spinning technique. The addition of Pd

to

Al-Y-Ni-Co alloys caused disappearance of the supercooled liquid region

as well

as the formation of the highly dispersed primary a-Al nanoparticles about 3-7 nm in

size homogeneously embedded in the glassy matrix upon solidification

(Fig. 8).

An extremely high density of precipitates of the order of 1024

m-3

is obtained. The

resulted d-spacings of a-Al in Al85Y4Ni5Co2Pd4

correspond very well to that of FCC Al.

The first direct observation of micro-strain and dislocations quenched in nanoparticles with a size below 7 nm was provided. Summary A large number of metallic glassy alloys undergo nano-devitrification on heating leading to the formation of nanoscale crystalline or quasicrystalline particles. In some alloys this effect leads to the formation of the nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties compared to fully glassy and fully crystalline alloys. Such alloys are being extensively studied at present and are believed to be important structural materials in the future. References: [1]. W. Clement, R. H. Willens and P. Duwez, Nature 187, 869 (1960) [2]. H. S. Chen and D. Turnbull, J. Chem. Phys. 48, 2560 (1968) [3]. H. S. Chen, Acta Metall. 22, 1505 (1974) [4]. A. Inoue, Mater. Trans. JIM 36, 866 (1995) [5]. W. L. Johnson, MRS Bull 24, 42 (1999) [6]. A. Inoue, Acta Mater. 48, 279 (2000) [7]. Nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, and applications, ed. A. S. Edelstein, R. C. Cammarata, Bristol, Institute of Physics Publ. 596 (1996) [8]. P. G. Le Comber, A. Madan and W. E. Spear, Electronic

and

Structural Properties of Amorphous Semiconductors. Ed. by P. G. Le

Comber and

J. Mort, Academic press, [9]. H. J. Fecht, Nanostructured Materials 6, 33 (1995) [10]. A.W. Weeber and H. Bakker, Physica B153, 93 (1988) [11]. R. Z. Valiev, Materials Science and Engineering A 234-236, 59 (1997) [12]. V. M. Segal, Mater. Sci. [13]. T. Yamasaki, P. Schlossmacher, K. Ehrlich and Y. Ogino, Nanostructured Materials 10, 375 (1998) [14] J. Ahmad, K. Asami, A. Takeuchi, D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Materials Transactions, 44, 1942 (2003) [15]. S. R. Elliot: Physics of Amorphous Materials, Longman

Group, [16]. B. Cantor, Materials Science Forum 307, 143 (1999) [17]. A. Inoue, K. Ohtera, A. P. Tsai and T. Masumoto, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 27, L280 (1988) [18]. A. Inoue, K. Ohtera and T. Masumoto, Jpn J Appl Phys 27, L1796 (1988) [19]. Y. He, S. J. Poon, and G. J. Shiflet, Science 241, 1640 (1988) [20]. A. Inoue and H.M. Kimura, Journal of Metastable and Nanocrystalline Materials 9, 41 (2001) [21]. A. Inoue, K. Ohtera, A. P. Tsai, and T. Masumoto, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 27, L736 (1988) [22]. A. Inoue, T. Zhang, K. Kita and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans. JIM 30, 870 (1989) [23]. A. Inoue, N. Matsumoto and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans. JIM 31, 493 (1990) [24]. D. V. Louzguine, and A. Inoue, J. Light Metals. 1, 105 (2001) [25]. D. V. Louzguine, A. R. Yavari and A. Inoue, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 316, 255 (2003) [26]. D. R. Allen, J. C. Foley and J. H. Perepezko, Acta Mater. 46, 431 (1998) [27]. A. Inoue and H.M. Kimura, J Light Met. 1, 31 (2001) [28]. A. Inoue, A. Takeuchi, Materials Trans. 43, 1892 (2002) [29]. W. H. Wang, C. Dong, C. H. Shek, Mater. Sci. [30]. J.F. Loffler, Intermetallics 11, 529 (2003) [31]. T. Zhang, A. Inoue, and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans., JIM 32, 1005 (1991) [32]. A. Peker and W. L. Johnson, Appl. Phys. Lett. 63, 2342 (1993) [33]. A. Inoue, Mater. Trans. JIM 36, 866 (1995) [34]. A. Inoue, W. Zhang, T. Zhang and K. Kurosaka, Acta Mater. 49, 2645 (2001) [35]. D. Xu, B. Lohwongwatana, G. Duan, W. L. Johnson and C. Garland, Acta Mater. 52, 2621 (2004) [36]. D. Wang, Y. Li, B. B. Sun, M. L. Sui, K. Lu, and E. Ma, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4029 (2004) [37]. A. Inoue, W. Zhang and J. Saida Mater. Trans. 45, 1153 (2004) [38]. P. J. Desré, Materials Transactions, JIM 38, 583 (1997) [39]. S. Pang, T. Zhang, K. Asami and A. Inoue, Materials Science and Engineering A, 375, 368 (2004) [40]. W. H. Peter, R. A. Buchanan, C. T. Liu, P. K. Liaw, M. L. Morrison, J. A. Horton, C. A. Carmichael, Jr. and J. L. Wright Intermetallics, 10, 1157 (2002) [41]. J. Schroers and W. L. Johnson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 255506 (2004) [42]. M. de Oliveira, W. J. Botta F., A. R. Yavari, Materials Transactions JIM 41, 1501 (2000) [43]. A. R. Yavari, M. F. de Oliveira, C. S. Kiminami, A.

Inoue and W.

J. Botta, Mater. Sci. [44]. T. Shoji, Y. Kawamura and Y. Ohno, Materials Transactions 44, 1809 (2003) [45]. Y. Kawamura, Т. Shibata, A. Inoue and T. Masumoto, Scripta Mater. 37, 431 (1997). [46]. M. Takagi, H. Iwata, T. Imura, Y. Soga, Y. Kawamura and A. Inoue, Materials Transactions, JIM 40, 804 (1999) [47]. D. Turnbull and M. H. Cohen J. Chem. Phys. 34, 120 (1961) [48]. A. Inoue and A. Takeuchi, Materials Transactions 43, 1892 (2002) [49]. Z.P. Lu and C.T. Liu, Acta Materialia 50, 3501 (2002) [50]. H. Tan, Y. Zhang, D. Ma, Y.P. Feng and Y. Li, Acta Materialia 51, 4551 (2003) [51]. D. V. Louzguine, L. V. Louzguina and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1556 (2002) [52]. L. Pauling, in The Nature of the Chemical Bond, Cornell Univ., USA, 3rd ed., 1960 p. 81 [53]. D. V. Louzguine, A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 3410 (2001) [54]. X.K. Xi, D.Q. Zhao, M.X. Pan and W.H. Wang, Intermetallics, in Press. [55]. J. D. Bernal, Proc. R. Soc. A., 280, 299 (1964) [56]. W. M. Visscher and M. Bolsterli, Nature 239, 504 (1972) [57]. D. B. Miracle, W. S. Sanders, O. N. Senkov, Phil. Mag. 83, 2409 (2003) [58] H. W. Sheng, W. K. Luo, F. M. Alamgir, J. M. Bai and E. Ma. Nature 439, 419 (2006) [59]. T. Egami and Y. Waseda, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 64, 113 (1984) [60]. S. Ueno, Y. Waseda, in: W. Lee, R.S. Carbonara (Eds.), Proceedings of the Rapidly Solidified Materials Conference, 1986, p. 153. [61]. C.H. Shek, Y.M. Wang and C. Dong, Materials Science and Engineering A291 78 (2000) [62]. Q. Jiang, B. Q. Chi, and J. C. Li, Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1247 (2003) [63]. M. H. Cohen and G. [64]. A. Van Den Beukel and J. Sietsma, Acta Metall. Mater. 38, 383 (1990) [65]. W. Kauzmann, Chem. Rev. 43, 219 (1948) [66]. E. Leutheusser, Phys. Rev. A 29, 2765 (1984) [67]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Mater. Sci. and [68]. K. F. Kelton, Mater. Sci. [69]. J.H. Perepezko and R.J. Hebert, J. Metall. 54, 34 (2002) [70]. J. H. Perepezko, R. J. Hebert, W. S. Tong, Joe Hamann, Harald R. Rösner and Gerhard Wilde, Mater. Trans. 44, 1982 (2003) [71]. J. H. Perepezko, R. J. Hebert and W. S. Tong, Intermetallics 10, 1079 (2002) [72]. A. N. Kolmogorov, Isz. Akad.

Nauk. [73]. M. W. A. Johnson, and K. F.

Mehl, Trans. Am. Inst. Mining. Met. [74]. M. Avrami, J. Chem. Phys. 9, 177 (1941) [75]. K. F. Kelton, J. Non-Cryst. Solids 163, 283 (1993) [76]. A. R. Yavari and D. Negri, Nanostructured Materials 8, 969 (1997) [77]. J. W. Cahn, Acta Metall. 9, 795 (1961) [78]. S. Schneider, P. Thiyagarajan, U. Geyer and W. L. Johnson, Physica B: Condensed Matter, 241-243, 918 (1997) [79]. A. K. Gangopadhyay, T. K. Croat and K. F. Kelton Acta Mater. 48, 4035 (2000) [80]. K. F. Kelton, T. K. Croat, A. K. Gangopadhyay, L. -Q. Xing, A. L. Greer, M. Weyland, X. Li and K. Rajan, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 317, 71 (2003) [81]. Y. H. Kim, A. Inoue and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans. JIM 32, 331 (1991) [82]. M. Gogebakan, P. J. Warren and B. Cantor, Mater. Sci. [83]. J. C. Foley, D. R. Allen and J. H. Perepezko, Scripta Mater. 35, 655 (1996) [84]. M. Calin, A. Rudiger and U. Koester, J. Metastable and Nanocryst. Mater., 8, 359 (2000) [85]. M. C. Gao and G. J. Shiflet, Intermetallics 10, 1131 (2002) [86]. Y. X. Zhuang, J. Z. Jiang, T. J. Zhou, H. Rasmussen, L. Gerward, M. Mezouar, W. Crichton, and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 4133 (2000). [87]. K. Hono, Y. Zhang, A. P. Tsai, A. Inoue and T. Sakurai, Scripta Mater. 32, 191 (1995) [88]. T. B. Massalski, Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams, ASM

International, [89]. A. R. Yavari and D. Negri, Nanostr. Mater. 8, 969 (1997) [90]. A. R. Yavari and O. Drbohlav Mater. Trans. JIM 36, 896 (1995) [91]. A. Mitra, H.-Y. Kim, D.V. Louzguine, N. Nishiyama, B. Shen, A. Inoue, Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 278, 299 (2004) [92]. H. Yoshizawa, K. Yamauchi, T. Yamane and H. Sugihara, J. Appl. Phys. 64, 6047 (1988) [93]. K. Suzuki, N. Kataoka, A. Inoue, A. Makino and T Masumoto, Mater. Trans., JIM 31, 743 (1990) [94]. K. Hono, Progress in Materials Science 47, 621 (2002) [95]. K. Hono, K. Hiraga, Q. Wang, A. Inoue, T. Sakurai, Acta Metall. et Mater. 40, 2137 (1992) [96]. W. J. Botta F., D. Negri, A. R. Yavari, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 247, 19 (1999) [97]. M. Ohnuma, K. Hono, H. Onodera, J. S. Pedersen and S. Linderoth, Nanostructured Materials 12, 693 (1999) [98]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Scripta Materialia 43, 371 (2000) [99]. G. He, J. Eckert and W. Loser, Acta Materialia 51, 1621 (2003) [100]. Z. Altounian, E. Batalla, J.O. Strom-Olsen, J.L. Walter, J. Appl Phys 61, 149 (1987) [101]. L. Q. Xing, J. Eckert, W. Loser, L. Schultz and D. M. Herlach Phil. Mag. A 79, 1095 (1999) [102]. D. V. Louzguine, H. Kato, H. S. Kim and A. Inoue, J. Alloys and Comp. 359, 198 (2003) [103]. D. V. Louzguine, L. V. Louzguina and A. Inoue, Philosophical Magazine 83, 203 (2003) [104]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Materials Letters 39, 211 (1999) [105]. D. V. Louzguine, M. Saito, Y. Waseda and A. Inoue,

Journal of the

Physical Society of [106]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Mater. Trans., JIM 40, 485 (1999) [107]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, NanoStructured Materials 11, 115 (1999) [108]. D. V. Louzguine, A. Takeuchi and A. Inoue Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 289, 196 (2001) [109]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue: Proc. 4-th Int. Conf.

IUMRS-ICA-97

(16-18 Sept. 1997, Mat. Res. Soc. Chiba, [110]. A. Inoue, Acta Mater. 48, 279 (2000) [111]. S. Schneider, P. Thiyagarajan, U. Geyer and W. L. Johnson, Physica B 241-243, 918 (1998) [112]. K. F. Kelton, Philos. Mag. Lett. 77, 337 (1998) [113]. J. W. Christian, The theory of transformations in Metals and Alloys, Pergamon Press Ltd., Oxford, 1975, p. 369. [114]. A. Peker and W. L. Johnson, Mater. Sci. [115]. N. Nishiyama and A. Inoue. Acta Mater. 47, 1487 (1999) . [116]. J. Loeffler, J. Schroers and W.L. Johnson. Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 681 (2000) . [117]. R. Janlewing and U. Köster, Mater. Sci. [118]. J. H. Kim, S. G. Kim and A. Inoue. Acta Mater. 49, 615 (2001) [119]. J. Schroers and W. L. Johnson, Mater. Sci. [120]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Scripta Materialia 47, 887 (2002) [121]. D. V. Louzguine-Luzgin and A. Inoue, Physica B: Condensed Matter, in press (2005) [122]. R.A. Grange, J.M. Kiefer, Trans. ASM 29, 85 (1941) [123]. H. Chen, Y. He, G. J. Shiflet, and S. J. Poon, Nature ( [124]. W. H. Jiang, F. E. Pinkerton, and M. Atzmon, J. Appl. Phys. 93, 9287 (2003) [125]. A. A. Csontos and G. J. Shiflet, Nanostruct. Mater. 9, 281 (1997) [126]. J.-J. Kim, Y. Choi, S. Suresh, and A. S. Argon, Science 295, 654 (2002) [127]. W. H. Jiang, F. E. Pinkerton, and M. Atzmon, Scr. Mater. 48, 1195 (2003) [128]. D. Shechtman, L. A. Blech, D. Gratias, J. W. Cahn, Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1951 (1984) [129]. A. Inoue, H. M. Kimura, T. Masumoto, J. Mater. Sci. 22, 1758 (1987) [130]. K. V. Rao, J. Fildler, H. S. Chen, Europhys. Lett. 1, 647 (1986) [131]. A. Inoue, L. Arnberg, B. Lehtinen, M. Oguchi, T. Msumoto, Metall. Trans. 17A, 1657 (1986) [132]. A. Inoue, H.M. Kimura, K. Kita, New Horizons in

Quasicrystals. ed.

by A. I. Goldman. D.J. Sordelet, P.A. Thiel and J.M. Dubois, World

Scientific, [133]. Y. Elser and C.L. Henley, Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2883 (1985) [134]. K.F. Kelton in Crystal Structures of Intermetallic Compounds, J. H. Westbrook and R. L. Fleischer Ed., John Wiley and Sons, New York, (2000), 229 [135]. J.Q. Guo, E. Abe, A.P. Tsai, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 39, L770 (2000) [136]. M. J. Kramer, S. T. Hong, P. C. Canfield, I. R. Fisher, J. D. Corbett, Y. Zhu, A. I. Goldman, J. Alloys and Comp. 342, 82 (2002) [137]. Y. Kaneko, Y. Arichika, T. Ishimasa, Phil. Mag. Lett. 81, 777 (2001) [138]. K. F. Kelton, Materials Science and Engineering A 375-377, 31 (2004) [139]. A. K. Srivastava and [140]. J. Saida, M. Matsushita and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 1287 (2000) [141]. K. F. Kelton, A. K. Gangopadhyay, G. W. Lee, L. Hannet, R. W. Hyers, S. Krishnan, M. B. Robinson, J. Rogers and T. J. Rathz Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 312-314, 305 (2002) [142]. K. F. Kelton, G.W. Lee, A. K. Gangopadhyay, R.W. Hyers, T. J. Rathz, J. R. Rogers, M. B. Robinson, and D. S. Robinson Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 195504-1 (2003) [143]. K.F. Kelton, J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 334-335, 253 (2004) [144]. Lj. Ouyang, D. V. Louzguine, H. M. Kimura, T. Ohsuna, S. Ranganathan and A. Inoue, Journal of Metastable and Nanocrystalline Materials 18, 37 (2003) [145]. U. Koster, J. Meinhardt, S. Roos, and H. Liebertz, Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 179 (1996) [146]. L. Q. Xing, J. Eckert, W. Loser, and L. Schultz, Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 2110 (1998) [147]. M. W. Chen, T. Zhang, A. Inoue, A. Sakai, and T. Sakurai, Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1697 (1999) [148]. A. Inoue, T. Zhang, J. Saida, M. Matsushita, M.W. Chen, and T. Sakurai, Mater. Trans. JIM 40, 1137 (1999) [149]. J. Saida, M. Matsushita, C. Li, and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3558 (2000) [150]. L. Wang, L. Ma and A. Inoue Mater. Trans. JIM 43, 2346 (2002) [151]. J. Saida and A. Inoue, J. Non-Crys. Sol. 312-314, 502 (2002) [152]. J. Saida, M. Matsushita, and A. Inoue, J. Appl. Phys. 88, 6081 (2000) [153]. B. S. Murty, D. H. Ping, M. Ohnuma and K. Hono, Acta Mater. 49, 3453 (2001) [154]. J. Saida, M. Matsushita and A. Inoue, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 342, 18 (2002) [155]. J. Saida, M. Matsushita and A. Inoue, Intermetallics 10, 1089 (2002) [156]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Applied Physics Letters 78, 1841 (2001) [157]. J. Z. Jiang, A. R. Rasmussen, C. H. Jensen ,Y. Lin, P. L. Hansen, Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 2090 (2002) [158]. E. Matsubara, M. Sakurai, T. Nakamura, M. Imafuku, S. Sato, J. Saida and A. Inoue, Scripta Materialia 44, 2297 (2001) [159]. A. R. Yavari, A. Le Mouleca, A. Inoue, W. J. Botta F, G. Vaughan and A. Kvick, Materials Science and Engineering A 304-306, 34 (2001) [160]. D. V. Louzguine, Lj. Ouyang, H. M. Kimura, A. Inoue, Scripta Mater. 50, 973 (2004) [161]. N. Chen, D.V. Louzguine, S. Ranganathan, A. Inoue, Acta Materialia 53, 759 (2005) [162]. D. V. Louzguine, M. S. Ko, and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3424 (2000) [163]. C. Li, J. Saida, M. Matsushita, and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 528 (2000) [164]. C. Li, J. Saida, M. Matsushita, and A. Inoue, Philos. Mag. Lett. 80, 621 (2000) [165]. D. V. Louzguine, M. S. Ko, and A. Inoue, Scripta Mater. 44, 637 (2001) [166]. C. Li and A Inoue, Mater. Trans. JIM 42, 176 (2001) [167]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue Annales de Chimie - Science des Matériaux 27, 91 (2002) [168]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Scripta Materialia 48, 1325 (2003) [169]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, J. Alloys and Compounds 361, 153 (2003) [170]. D. V. Louzguine, H. Kato, A. Inoue, Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 4, 327 (2003) [171]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, J. Mater. Res. 17 (2002) 2112 [172]. J. Z. Jiang, B. Yang, K. Saksl, H. Franz, and N. Pryds, J. Mater. Res. 18, 895 (2003) [173]. M. Kasai, J. Saida, M. Matsushita, T. Osuna, E. Matsubara, and A Inoue, Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 14, 13867-77 (2002) [174]. D. V. Louzguine, A. R. Yavari and A. Inoue, Philosophical Magazine 83, 2989 (2003) [175]. Y. Chen, T. Zhang, W. Zhan , D. Ping, K. Hono, A. Inoue and T. Sakurai, Materials Transactions. 43, 2647 (2002) [176]. D. V. Louzguine, A. R. Yavari and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 041906-1 (2005) [177]. A. Inoue, T. Zhang, M. W. Chen, T. Sakurai, J. Saida and M. Matsushita, Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 967 (2000) [178]. S. Takeuchi, Quasicrystals, Sangyotosho, [179]. A. Inoue, C. Fan and A. Takeuchi, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 250-252, 724 (1999) [180]. A. Inoue and C. Fan, Nanostructured Materials, 12, 741 (1999) [181]. J. Eckert, U. Kühn, N. Mattern, A. Reger-Leonhard and M. Heilmaier Scripta Materialia, 44, 1587 (2001) [182]. M. Heilmaier, Journal of Materials Processing Technology 117, 374 (2001) [183]. A. Inoue, C. Fan, A. Takeuchi, Mater Sci Forum 307, 1 (1999) [184]. T. C. Hufnagel, Cang Fan, R. T. Ott, J. Li and S. Brennan, Intermetallics 10, 1163 (2002) [185]. D. V. Louzguine, H. Kato, and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1088 (2004) [186]. C. Qin, W. Zhang, H. Kimura and A. Inoue, Mater. Trans. 45, 2936 (2004) [187]. A. Inoue, K. Ohtera, A.P. Tsai and T. Masumoto, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 27, L280 (1988) [188]. A. Inoue, K. Ohtera, A. P. Tsai and T. Masumoto, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 27, L479 (1988) [189]. G.J. Shiflet, Y. He and S.J. Poon, J. Appl. Phys. 64, 6863 (1988) [190]. Y.H. Kim, A. Inoue and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans., JIM 31, 747 (1990) [191]. Y. H. Kim, A. Inoue and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans. JIM 32, 599 (1991) [192]. A. Inoue and H.M. Kimura, Mater. Sci. Forum 235-238, 873 (1997) [193]. Y.-H. Kim, A. Inoue and T. Masumoto, Materials Transactions JIM 32, 331 (1991) [194]. A. Inoue, K. Nakazato, Y. Kawamura, A. P. Tsai and T. Masumoto. Materials Transactions, JIM 32, 331 (1991) [195]. A. Inoue, K. Nakazato, Y. Kawamura, A.P. Tsai, T. Msumoto. Mater. Trans. JIM 35, 95 (1994) [196]. D. V. Louzguine, A. Inoue, J. Mater. Res. 17, 1014 (2002) [197]. A. Takeuchi and A. Inoue, Mater. Trans., JIM 41, 1372 (2000) [198]. Y.H. Kim, A. Inoue, and T. Masumoto, Mater. Trans. JIM 32, 599 (1991) [199]. H. Chen, Y. He, G.J. Shiflet and S.J. Poon, Scripta Mater. 25, 1421 (1991) [200]. K. Pekala, P. Jaskiewicz, J. Latuch and A. Kokoszkiewicz, J. Non-Cryst. Solids 211, 72 (1997) [201]. N. Bassim, C. S. Kiminami and M.J. Kaufman, J. Non-Cryst. Solids 273, 271 (2000) [202]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 311, 281 (2002) [203]. D. V. Louzguine and A. Inoue, Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3061 (2001) [204]. D. V. Louzguine, A. Takeuchi and A. Inoue, Journal of Materials Science 35, 5537 (2000) |

||||||||||||||||||

|